Henry Bialowas - Author

As a Heritage architect, Henry found himself drawn into the history of the Ribbon Gang. Although he had no ambition to write book, much less one about bushrangers, the unresolved story intrigued him. The result of his researches both here and the British Isles, and the encouragement of Marie Sullivan OAM, led to the publication of Ten Dead Men. The manuscript drew the attention of the Late Allen Bardsley, a British filmmaker, who was working on a project with Marie at the time.

This led to his writing a screenplay for a feature film. Sadly, Allan Bardsley passed away within days of receiving the script. Henry is now working with another filmmaker.

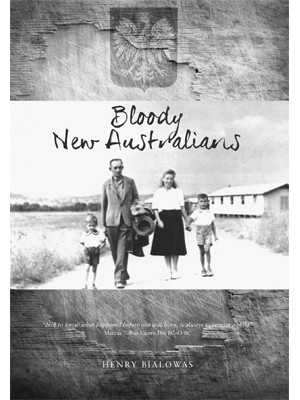

Henry has since written a Memoir, which is about to be published and titled, Bloody New Australians tells of his arrival in Australia as a three year-old migrant in 1950, his parents having been Polish captives in a war torn-Germany under Hitler.

Ten Dead Men

Ten men were hanged in Bathurst NSW in 1830. It was the first and largest execution to be held in the town and arguably in Australian history. The condemned were the last of the ‘The Ribbon Gang’. They were a group of convicts who absconded from their masters, killing an overseer and were purported to number one or two hundred strong. They were pursued for three weeks by a coalition of troops, mounted police and citizen posses numbering some two hundred.

Ten men were hanged in Bathurst NSW in 1830. It was the first and largest execution to be held in the town and arguably in Australian history. The condemned were the last of the ‘The Ribbon Gang’. They were a group of convicts who absconded from their masters, killing an overseer and were purported to number one or two hundred strong. They were pursued for three weeks by a coalition of troops, mounted police and citizen posses numbering some two hundred.

In the days leading up to their capture their numbers had dwindled to some twenty, at best thirty men. They fought a series of running gun battles. In the final days, three of the gang were wounded and captured. Lieutenant McAlister leading the party was shot in the thigh during the skirmish. A ticket-of-leave constable Daniel Geary was also seriously wounded before the prisoners were taken to Bong Bong. Among the casualties was also, a James Stephens, who died from gunshot wounds several months later. Finally, ten men were returned to Bathurst to face a staged trial with a predetermined outcome.

Here was a tale suggested more by what was omitted than by what was included in the often dry factual newspaper accounts; the recollections of details some fifty years after the event. Why so large an uprising should be so briefly treated in the history of this region, was puzzling.

In Ten Dead Men Henry sets out to provide an explanation of the tragedy by reconstructing the context in which these events took place. In doing so, He reveals the circumstances, the people and their backgrounds and how those factors inevitably led to the distortion of the truth. The fact that none of the ten men who paid the ultimate price could write, leaves only the official records which are heavily biased towards the ruling class of the time.

It is a re-examination of a brief yet critical moment in our Colonial history. The arrival of Ralph Darling, who almost immediately falls out with the elite, the press, the Judiciary and who fans the flames of the already tense sectarian struggles between the Catholics and Protestants.

The factional struggles throughout that microcosm of society at the crucial time when land was becoming readily available, lead to rapacious activities at all levels of society from those in Government making decisions in Whitehall, to those in office in the Colony from the Governor down to the lowly convicts.

He describes those in power; in particular, the corruption of magistrates, and the blatant deceptions used on the Governor himself, to cover up the cruel practices and injustices that lead to the convict uprising.

The story deals with the shattered hopes and aspirations of convicted men women and children sent to the Colony, often for the most trivial of reasons.

The incessant struggle for power and wealth among the privileged, often to overcome past failures, disinheritances and short comings in England, continued here in the Colony, but with the difference that they were now in charge and unfettered by rules, regulations which they themselves were policing.

The story centres on the leader of the gang, Ralph Entwistle, convicted for stealing clothing. Entwistle finds himself in the vice ridden hulks where sodomy and male rape are openly practised, he grimly awaits his transportation to an unknown world for life. The former apprentice brick-maker from Bolton, finds himself with a glimmer of hope by being promised a ticket-of-leave. It is what makes him aspire to ‘buy land and marry a wife’ but then he falls victim to the merciless drive for wealth by the gentry in the midst of a three-year drought that devastates the region and changes the ground rules of survival of the most opportunistic.

The degree of indifference to convicts by the landowners, many of who were also the magistrates, plummeted to a new low. Their Machiavellian endeavours brought them to a deceptive charade before the visiting Governor who was duped into seeing only their point of view. The Vice-Regal visit became the turning point for the hapless convicts who were pushed closer and closer to that precipice of last resort, rebellion.

Bloody New Australians

In Bloody New Australians, Henry, who was born in Germany and spent his first three years in a former concentration camp, recalls his early life in 1950’s Australia. His Polish parents were both captives of Hitler’s Germany during the Second World War and having survived, were invited to Australia as migrants. In this memoir, Henry traces the family’s stories of survival and hardship through the turbulent years of recent Polish history.

In Bloody New Australians, Henry, who was born in Germany and spent his first three years in a former concentration camp, recalls his early life in 1950’s Australia. His Polish parents were both captives of Hitler’s Germany during the Second World War and having survived, were invited to Australia as migrants. In this memoir, Henry traces the family’s stories of survival and hardship through the turbulent years of recent Polish history.

His great grand father experienced the devastation of the Napoleonic army as it marched through Poland to near annihilation at the gates of Moscow. His grandmother died during childbirth leaving a two-year-old child who would later become his father.

His father’s early years were spent surviving the First World War, a fatal flu epidemic, which killed millions, as well as outbreaks of cholera and typhoid, before leaving home at the age of eleven.

In his teens he witnessed at first hand the Polish-Russian war and was almost killed during a riot and political coup in Warsaw some years later.

At the outbreak of the Second World War, Henry’s mother was abducted by the Gestapo on her sixteenth birthday and spent the entire six-year war as slave labour on a German farm.

His father was also taken to Germany and put to work in a factory and later punished for a misdemeanour by serving a time in Bergen Belsen.

Reflecting on these events, Henry examines the belief systems that created and sustained the various regimes that were responsible for the greatest devastation cruelty and mass murders that the world has thus far endured to this day. It is perhaps a lesson for our time as well, as he argues that history does repeat itself by the uncritical acceptance of ideologies. A fact all too clear in today’s terrorist plagued world.

He argues that blind adherence to ideologies has been and continues to be the flaw in our societies. And the uncritical acceptance of what our politicians and leaders of all persuasions, would like us to believe, is the base cause of the troubles we collectively face. Our past continues to haunt us today and will likely continue until we consciously examine our beliefs and the basis for those beliefs.